Overview

Twenty-first century philanthropy has a successful donor-model to distribute common wealth benefits to local communities: the Carnegie Free Libraries model. The US Steel magnate Andrew Carnegie provided an idea (free libraries) and a model (general architectural and public support terms) in which he could distribute his enormous wealth as a gift to the commons sector. Within two decades, close to two thousand Carnegie Libraries were built across the United States. Solar Commons could also pop up around the country as a new public face for the regenerative common wealth that renewable energy can bring to local communities. The Solar Commons Project is creating administrative capacity around the Solar Commons Community Trust Ownership Model so that donors can quickly and confidently distribute the gifts of their wealth to low-income communities who empower themselves through the civic tools of Solar Commons Trusts.

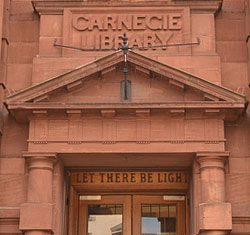

Let There Be Light: Scaling Solar Commons Like Carnegie Libraries

Given the urgency of climate change and social equity needs, the Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) analyzed the capacity of the Solar Commons Model to scale its model over the near future in the US serving both climate and social equity through its donation model. (Read the RMI scalability capacity here.) RMI found that the ideal size of a Solar Commons array is 500kW (larger sizes create administrative overhead that reduce the benefits to the community trust). Over ten years, Solar Commons could proliferate in cities and towns across the US and achieve a minimum of 10 gigawatts or 20,000 community-based Solar Commons of 500kW each providing between $100,000 and $70,000 (depending on the region’s solar capacity and net-metering rates) a year for twenty years to each community social trust fund. There is already a successful donation model for this scaling strategy accomplished by another innovation linked to expanding democracy through America’s social infrastructures over a century ago: the Carnegie Library model.

Yesterday

Yesterday

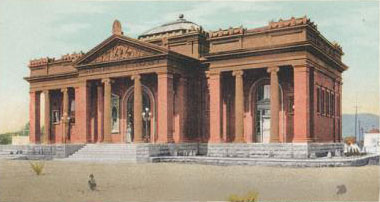

At the turn of the twentieth century, the Carnegie Endowment sought to support democratization of knowledge by building over 1,500 “free libraries” in cities and towns throughout the United States. The free Carnegie Libraries were a gift of US Steel magnate, Andrew Carnegie, who maximized his Gilded Age wealth for the common good by outlining key principles of open-access, open-shelf library design and providing grants to communities willing to build and steward such “free libraries.” The Carnegie Foundation worked with local organizers—often women’s clubs partnering with local government officials to locate sites and other in-kind supports—and within a span of decades helped institutionalize these new “open shelf” access practices that further democratized how public libraries served local communities in the United States. (See Abigail Van Slyck, Free to All: Carnegie Libraries & American Culture, 1890-1920 [1995]). Taking its cue from the success of the Carnegie Libraries, Solar Commons Project researchers are developing the Solar Commons Trust Ownership Model to provide administrative tools that bring similar, simple design principles and civic governance tools so that Solar Commons can be a reliable source for funders to democratize solar energy over the next decade in the United States. Solar Commons Project (SCP) researchers are thus:

- designing and testing flexible and clear trust guidelines and open-source legal templates that make the Solar Commons Community Trust Model a vehicle for large, Carnegie-like donors to partner with low-income community program providers to fund Solar Commons projects in rural and urban areas across the US.

- co-creating with low-income community members in a “living lab” method, the neighborhood engagement processes and digital dashboard tools that are the “architecture” or “infrastructure” for Solar Commons to prove its effectiveness as a “commons option,” local, transparent, community-governed ownership model for the solar energy sector.

- providing demonstration sites and processes for educational, place-making public art that defines the neighborhood as a Solar Commons beneficiary and celebrates their stakeholder status in the equitable title to the sun’s common wealth.

- institutionalizing the standards and guidelines whereby trust law can evolve the function of “trust protector” to serve the interests of Solar Commons beneficiairy communities with clarity for all parties using a Solar Commons Trust agreements.

Just as Carnegie library architects were given general and flexible design principles to incorporate democratic ideals of knowledge-sharing—open shelf access; loft structures to designate the “higher” ideals of enlightenment knowledge–into the library building structure, communities developing a Solar Commons Community Trust would have similar guidelines and structures to connect solar energy to earth stewardship, common wealth, and social equity. Based on ancient legal precedent, Solar Commons researchers know that community stakeholders benefiting from feudal energy commons of peat and wood celebrated their equitable interests in the earth’s energy gifts in yearly festivals, local saints’ days, and local village fairs. Modern legal forms of community ownership can also be more powerfully and meaningfully iterated and scaled using both technical documents and joyful celebrations. The Solar Commons Project is developing the tools to iterate a culturally rich, legally secure, and transparently, equitably governed form of solar common wealth for the urgent times we face today.

Carnegie libraries have lasted in various forms for three generations. Solar Commons Trusts will last as long as is stipulated in the trust agreement, generally a period given by the solar technology itself: twenty-five to thirty years. But once the practice of “Solar Commoning” is recognized in local communities and the role of Solar Commons trust protectors is institutionalized in all states, Solar Commons can continue to iterate and scale throughout the twenty-first century in legal and cultural forms that articulate its democratic, regenerative vision of energy commons in sync with earth commons.

Despite its very different material form from the brick and mortar of a Carnegie library, the “public face” that community stakeholders and funders co-create for Solar Commons will nevertheless offer an opportunity for general, democratic principles informing the common good to be adapted to local, contemporary realities. Carnegie libraries are all different; local architects designed them to look like the places where they were built. Solar Commons Trusts will likewise adapt principles of local, equitable energy ownership to meet the diverse needs of twenty-first century life that arise differently for diverse communities. The diversity of Solar Commons adaptations should also be visible in the community’s Solar Commons public art.